Tunnels do little to enhance the passenger experience, turning off the daylight and mobile phone signals. For some, this seemingly results in personal crisis. Any sense of what it took to drive the tunnel – in either human or engineering terms – is lost in the transient frustration. But then it’s hard to see the bigger picture when you’re in the dark.

Whilst modern machinery allows tunnelling to proceed with little manpower and relative ease, things were very different historically. Every one of the 695 bores on our ‘classic’ network represents a victory over the collective forces of earth, water and Murphy’s Law. Some of those victories bordered on miraculous; almost all proved costly.

Tortoise or hare?

Plans to connect the manufacturing towns of Leeds and Bradford by rail first appeared before Parliament in 1830, the intention being to improve transport links for the latter’s burgeoning wool trade. Although direct, the 91⁄2-mile line involved stiff gradients, with a 1:30 incline at the western end worked by a stationary engine.

Its promoters got cold feet when inflated costings emerged, causing the Bill to fail. A second scheme was put forward in 1839, but the necessary funding was not forthcoming.

Four years on, it took an intervention by George Hudson, ‘The Railway King’, to re-energise the idea. Consulting engineer Robert Stephenson surveyed a route along the Aire valley, entering Bradford from the north. Being four miles longer than the original line, business leaders opposed it with some vigour; but, as Stephenson explained to the Parliamentary committee, its ruling gradient of 1:200 was more suited to the under-powered locomotives available at the time, meaning end-to-end journeys would actually be quicker and cheaper to operate than via a more direct route.

Royal Assent came in July 1844. However, raising sufficient capital proved problematic; then Hudson offered a guaranteed return of 71⁄2 per cent and suddenly found himself beating prospective investors off with a stick. Staking out the line got underway immediately, although the brightest spotlight was shone on Thackley Hill – an obstruction to be overcome by a 1,364-yard tunnel. Here, seven shafts were started under the supervision of Francis Mortimer Young, the resident engineer. The following January, a contract for the substantive works was awarded to Messrs Nowell & Hattersley. They would benefit to the tune of £68,000, the equivalent today of about £7.8 million.

Fatal attraction

The islands of industry, 250 yards apart, that transformed the landscape around each shaft must have been a source of great curiosity. Locals would never have seen anything like it. Deployed at one was a 25HP condensing steam engine, used to lower men and materials into the workings and bring spoil out. It had a pump motion for a double lift and, alongside it, stood a 30HP cylindrical boiler.

Death loitered nearby whenever shafts were sunk, ready to exploit any error of judgement or momentary lapse. Typical of those lost at Thackley was George Hardage – a miner, aged 19 – who fell down a shaft on Thursday 5 June 1845. Baptist preacher Alexander Pitt attended his funeral, addressing almost 2,000 mourners who had gathered outside the New Inn in Idle, where Hardage lay. Pitt recounted that “A solemn silence pervaded the whole meeting; all seemed to feel the solemnity of the occasion. Most of his fellow workmen were present; they, too, appeared much affected. I observed tears trickling down the cheeks of several of them.”

And then there was the gruesome case of gaffer William Hervey who had secured a 15cwt stone to the rope at the bottom of No.6 shaft prior to it being hoisted out. On two or three occasions, the ageing engine proved unequal to the task despite pieces being broken off to lighten the load. Hervey went up to investigate; thereafter the stone was reattached and a further attempt made. When it stopped again at the half-way point, he went to the flywheel, put his foot on one spoke and firmly grasped another, intending to help it forward. However the wheel turned the other way, trapping Hervey’s head and legs in a three-inch gap between the wheel and a wall behind it. He was heard to exclaim “Oh God, stop it”, but death followed almost instantaneously.

In both these cases, inquest juries returned verdicts of “accidental death”; it was common for the unfortunate casualty to shoulder the blame for their demise, whether warranted or not. This provoked a correspondent of the Bradford Observer to assert that “while shareholders are pocketing their six, or eight, or ten per cent, there are widows and fatherless children lamenting – in bare, hunger-visited hovels – the loss of their natural protectors. Does not natural justice suggest that railway proprietors should make some compensation in such cases?”

A different world

The social scene could not have been more contrasting on Tuesday 30 June 1846, the occasion of the line’s formal opening. Along its length, crowds turned out to witness the spectacle, cheering and waving flags. A train bearing shareholders and other dignitaries departed Leeds at noon on a journey taking 45 minutes. Awaiting them in Bradford – where all business had been suspended – was a temporary pavilion, its walls adorned with paintings including one of a train entering the tunnel.

In the teeth of an unseasonal storm, Mr and Mrs Harrison from the Sun Inn catered for a thousand guests with 20 joints of beef, 36 pigeon pies, 24 hams, 20 lambs, 54 ducks, 60 chickens, 24 tongues and 40 lobsters. In his address to those feasting, George Hudson commended the “contractors, artisans and labourers” whose “energy and spirit” had ensured completion of the line in just 16 months.

Business as usual

As built, Thackley tunnel extended for 1,496 yards, 132 yards longer than initially planned. Five of the shafts were retained for ventilation purposes. From the outset, third class passengers in open carriages complained vigorously about the drenching they received from penetrating groundwater, prompting a promise from the directors to attach protective metal sheeting to the stonework, although there’s no evidence they ever did.

The tunnel continued to play out scenes of misadventure despite its operational status. A soldier and vicar separately met their ends within its limits, as did ganger Ben Smith. There were derailments, flood events and a bizarre concocted robbery, whilst commercial traveller Walter Stevens fell out of his compartment at 40mph and spent the next two hours evading trains as he crawled towards the exit with a smashed knee.

In July 1897, the Midland Railway’s Works Committee resolved that a second bore was needed to cope with increasing traffic and its impact on ventilation. The ‘Thackley Widening Act’ received Royal Assent the following year, allowing work to proceed on the new bore under the auspices of engineer J A McDonald and Thomas Oliver & Sons, the contractor. It opened on 27 January 1901 and remains a key structure on today’s Airedale Line, connecting Leeds to Bradford, Skipton and beyond.

On the move

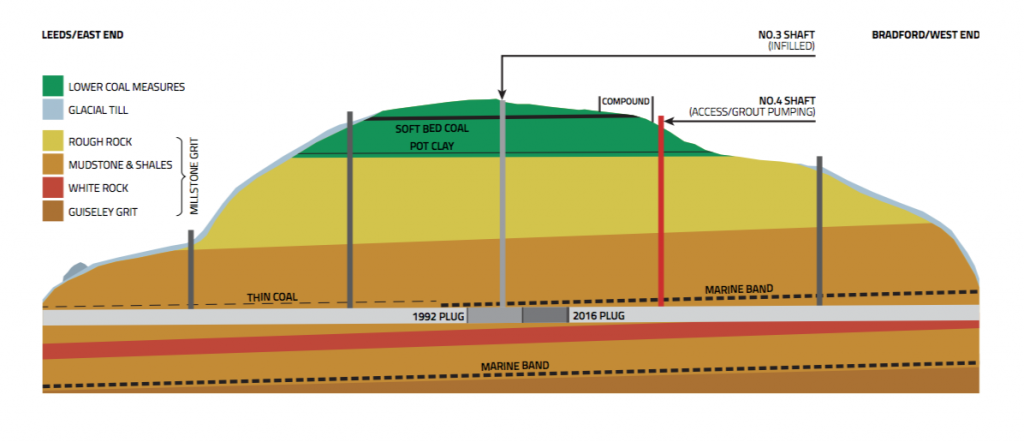

Thackley’s original tunnel entered its current period of disuse in 1968, although it continues to be subject to Network Rail’s asset management regime. In April 1985, a bulge was recorded at the haunch closest to the live bore (north/Up side) which was braced with steel ribs whilst monitoring took place. Further support was added as the rate of movement reached 4.5mm per annum; subsequent examinations also identified a 4.9 metre transverse fracture – open by one inch – together with a smaller bulge on the Down side.

Core drilling and endoscopic investigations suggested that the material behind the bulge was mudstone; evidence was found of the timbers that had been used to prop it during construction. A study of the local geology indicated a mudstone unit dipping towards the tunnel from the north/north-east, capable of imposing load on the lining due to its depth but steep enough to pass over the New bore without affecting it.

In 1992, two blockwalls were built and the 83-yard section of tunnel between them grouted – together with No.3 shaft – to prevent further deterioration. However, in 2013, more distortion was recorded immediately to the west, with the crown being forced upwards into a void as the high haunches were pushed inwards. This brought concerns that consequential defects may emerge in the operational bore which would be difficult to remediate due to the presence of overhead line equipment.

The solution was another infilling project, this time over a distance of 67 yards. Lasting 12 weeks, the works were progressed by AMCO Rail through the summer of 2016. The design work was fulfilled by Donaldson Associates.

Now you see it

Secured as a compound was a parcel of land owned by Bradford City Council, normally used as a working livery by a nearby equestrian centre. Within it stands No.4 shaft. Over seven days, a large-scale grouting station was established here incorporating storage tanks and pumping equipment. Ainscough provided a 100-tonne crane to do the heavy lifting.

To reach the west portal, plant and materials had to be transported almost three miles, much of it along a lineside track. However, Apollo Cradles was engaged to install a platform which allowed the workforce to enter and leave the tunnel via the shaft, accessed from a scaffold wrapped around the protection wall. They also secured three 63mm-diameter grout delivery pipes to the shaft lining with bespoke fixings.

In the tunnel, to draw water away from the live bore and shafts, 90 holes were drilled into the rock behind the lining – each eight metres deep – and a conduit installed which was sealed with foam and held in place by stainless steel brackets.

As well as ventilation pipes, pairs of 300mm diameter drains pass through the pre-existing plug at the toe of the sidewalls. CCTV inspections found that these had become blocked during the original grouting operation, so one on each side was reamed out to restore the water flow. Both the ventilation pipes and drains were then extended through the section to be infilled, the joints being double- sealed. The pipes were fastened to the lining at the haunches and chained down to prevent buoyancy.

No way out

Lengthy discussions had taken place between Donaldsons and AMCO as to the most appropriate fill material. Foam concrete was favoured at an early stage as it could be batched and pumped; it is also very light, imparts relatively little load but is strong enough (0.5- 1N/mm2) to resist deformation of the lining. However, it has to be poured in one-metre layers and the chemical reactions, when setting, generate a huge amount of heat. This would prove difficult to dissipate due to the confined nature of the tunnel.

Given the expected forces and the eventual likelihood of a lining failure, other products offering less strength were soon ruled out. It was ultimately decided that Fresh Cement Bentonite Grout from Bachy Soletanche met the various requirements, with a density of 1,120-1,130kg/m3 and strength of 1-2N/mm2. A required quantity of 2,540m3 was estimated.

To allow for a continuous pour whilst addressing its loading implications, a double-diaphragm wall was built on a >300mm thick reinforced concrete slab using 10.4N/mm2 blockwork in Flemish bond. The two-metre interior space was then filled with G3 grout placed in 900mm lifts. A system of dowels and fixings tied together the wall, its foundation and the tunnel arch/ sidewalls. Prior to construction, Wilkit foam had been injected radially through holes drilled at 500mm centres to fill any voids behind the lining around the bulkhead, thus preventing grout migration during the main pour.

Two sets of four pipes passed through the wall at the crown; these were extended by various lengths into the fill area to ensure an even distribution of grout. In total, 2,406m3 was pumped down the shaft and into the tunnel – a distance of around 300 metres – over six days, the operation involving 24-hour working apart from a break over the August Bank Holiday weekend. Within a week, the site had been demobilised, rotovated and reseeded.

All due respect

Those who can appreciate the industry involved in constructing Thackley’s first tunnel might view with some discomfort the act of partially infilling it, seeming somehow disrespectful to the men who contributed to its excavation. Of course, last year’s work was justified by the imperative of protecting the parallel live bore. AMCO Rail undertook the task with typical proficiency, its workforce earning praise from neighbours for their helpfulness and courtesy. In this case, that’s the bigger picture.

Thackley’s potential usefulness ended 25 years ago when the first plug was shortsightedly inserted without the provision of through access. Since then it has effectively been two tunnels, each with one end. What’s the point in that? You’d like to think though – given today’s more enlightened approach to the preservation of our engineering heritage – that not every redundant tunnel will suffer a similar fate.

Written by Graeme Bickerdike

Photos: Four by Three