Following on from David Shirres’ article in issue 184 (May/June 2020), the Railway Industry Association staged a week-long webinar to explore how innovation can help the transition to a Digital Railway. Held online between 29 June and 3 July, the sessions explored various elements on introducing digital systems, but mainly concentrated on how the ERTMS project would roll out on the East Coast main line and other routes thereafter. Interesting views and challenges came across, but one thing is for certain, it will not be easy.

I first reported on the Digital Railway in September 2015, when the concept was to make all railway operations and business more efficient by the adoption of digital techniques. This proved too ambitious and failed to recognise the significant problems of implementation.

A second article appeared in January 2017, when the newly appointed David Waboso gave his more realistic view on the elements that would make a successful digital railway. ETCS featured prominently, but the progress made since then has not met expectations. In the same edition, Adrian Shooter outlined some innovative projects of the past, most of which were abandoned because of technical and delivery difficulties – the APT (Advanced Passenger Train) being the most prominent.

So, what is different now? The following commentary will hopefully give some answers.

New structure

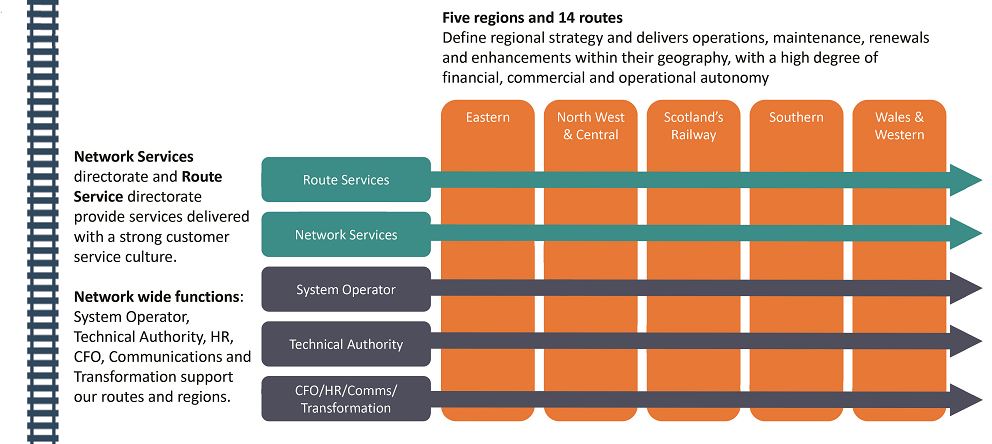

Network Rail has long recognised that the digital railway would need a centralised strategy for implementation. However, with its mainstream organisation now focussed on five Regions and 14 Routes, harmonising central and local interests will need the appropriate diplomacy.

Nick King is director of Network Rail’s Network Services group, which aims to pull together Route Services, Network Services and Systems Operations into a Technical Authority that will steer the introduction of digital technology.

The group needs highly skilled expertise and is likely to expand from the present 180 people to 1,500. It will include Network Rail Telecoms (NRT), seen as a key element in connecting it all together.

Six ‘pillars’ make up the group’s focus:

I – Network strategy and operations

II – Passenger interests

III – Freight interests

IV – NRT

V – Operations project delivery

VI – Signalling innovations including testing and commissioning.

The Department for Transport (DfT) supports this model as a Sector Plan.

Improving track-worker safety and reducing trespassing are still important, as the recent tragic incidents such as Margam and Roade show. 10,000 people work on or near the track every day, but only 26 per cent of the tasks undertaken are completed with line blocks or additional protection. 16 per cent happen in red zones with unassisted look out facilities, 16 per cent are completed without the protection method being recorded.

On a railway which has 60 per cent higher track utilisation than most of Europe, a move towards intelligent infrastructure is long overdue. As one track engineer remarked: “Data, data everywhere, but not a drop to use.”

Whilst some of the benefits of a move to risk-based maintenance are being realised, infrastructure faults still cause massive delay. Using data streams for intelligent decision making, coupled with aerial (drone-based) surveys, could make a big difference.

Is the rail industry successful in introducing new technology? In general, the answer is NO. Many legacy data systems exist, for example TOPS and TRUST, but they have no clear owner, which prevents them being updated and acts as a deterrent to the adoption of more modern data formats.

Is there insufficient industry leadership, the so-called directing minds? An all-industry approach is required to specify what is needed. Technology must be kept up to date, with better use of the engineering elements, for instance using the signalling system to show how the track asset is conditioned. Maybe artificial intelligence (AI) will help, but data silos remain a big risk.

Digital Railway components

Andrew Simmons, the chief systems engineer for Network Rail’s Digital Railway, has a background in signal engineering, but is now tasked with widening the signalling elements into fully digital command and control systems. He listed these as:

- Safe separation of trains – ETCS

- Train movement control – C-DAS

- Traffic management

- Telecoms & data – the NRT fibre and radio networks.

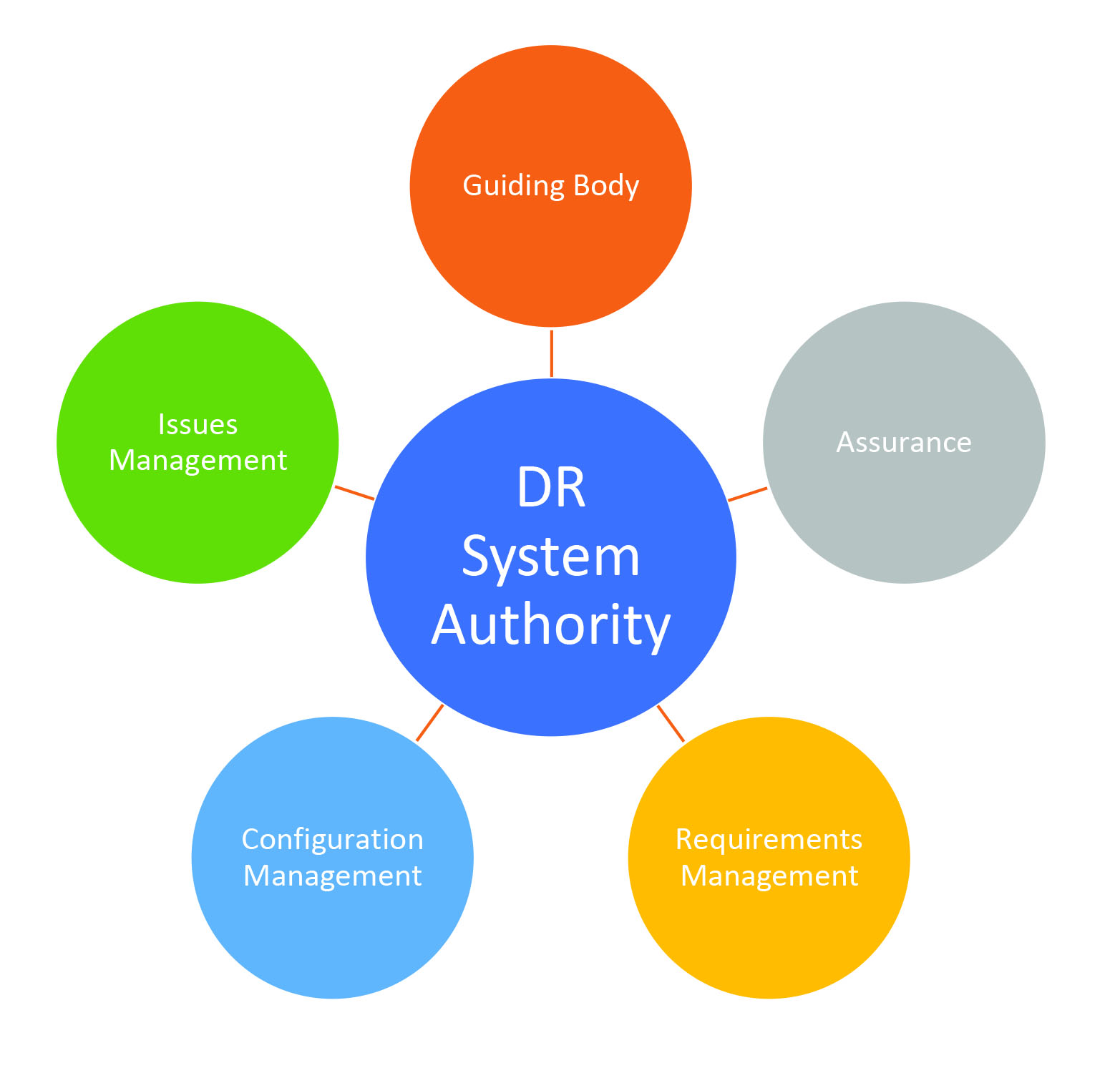

All need skills, capabilities and business change to successfully link into a Digital Railway Systems Authority, which has been a concept since 2017 and is now fully operational. But what is a Systems Authority? It is the body that will give a high-level steer but, beneath it, there has to be a:

I – Technical Authority

II – Design Authority

III – Technical Systems Integrator

IV – Rail Systems Integrator

V – System Users Group.

A whole industry and whole systems approach is necessary for these to be achieved and will lead to a whole life cost realisation plus safety and security enhancements.

Even with these in place, at implementation level there needs to be a Guiding Body to produce the technical strategy, an Assurance Function to carry out checks and balances, a Configurations Management to integrate other systems, an Issues Management to deal with emerging problems and a Requirements Management for verification and validation.

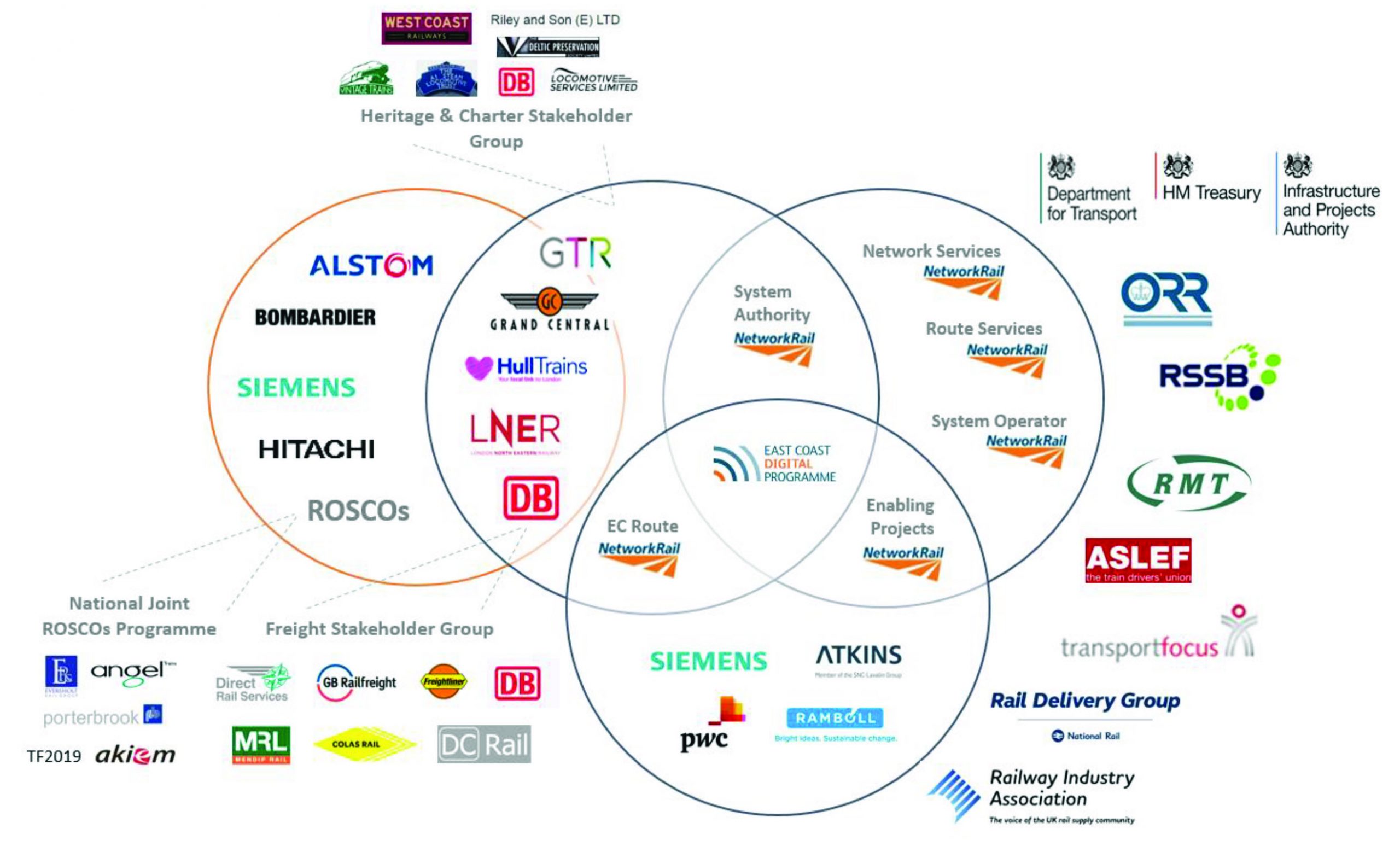

The overall Authority Governance will rest with Network Rail, the Rail Delivery Group and RSSB with input from train and freight operators (TOCs and FOCs), rolling stock leasing companies and the Network Rail routes. The plan is to bed the digital systems in on the ECML and trans-Pennine routes, then turn the results into RSSB standards.

One could be forgiven for commenting that this is interoperability in its ultimate form!

East Coast main line

ETCS on the ECML will not be the first applications of this technology in the UK. The Cambrian line was converted as long ago as 2010, then came Thameslink with ATO superimposed on to it (another UK first) and the GWML being in the installation phase from Heathrow Airport to Paddington as an overlay to the lineside signals to cater for non-fitted trains. The ECML is thus the first mainline application where lineside signals will be removed.

Toufic Machnouk, Network Rail’s route programme director, explained the project and some of the challenges. ETCS will extend from London King’s Cross and Moorgate to Stoke tunnel, just short of Grantham, around 100 miles in length. It is essentially a renewals project, but capacity and performance gains will be made. In addition to Network Rail, other bodies involved include four TOCs, seven FOCs, the supply chain, the trade unions, the government and the safety authorities. The experience gained from previous UK projects will be taken into account, as will lessons learned from European countries – Denmark, Norway, Netherlands – plus also the National Air Traffic Services (NATS) project.

Success will be more about people than technology, with the partnership between track and train being crucial. The project will proceed in five tranches:

- The Northern City line between Finsbury Park and Moorgate in London, this being a self-contained section mainly in tunnel;

- Provision of ETCS as an overlay to the existing signalling, mainly for driver training;

- Provision of a Traffic Management System;

- Progressive roll out including train fitment;

- Optimisation and clarification with eventual removal of lineside signals.

The biggest challenges are seen as:

I – Retro-fitting the legacy fleet including on-track machines;

II – Intelligent timetable development for both a high speed and mixed traffic railway;

III – Business capability and response to change;

IV – Credibility and affordability.

The government has signified its approval.

LNER perspective

The main East Coast TOC has seen at least three changes of ownership in recent years. Paul Boyle, the head of ERTMS for LNER, has been in place through all this and has given talks at past conferences to tell of the TOC position. He must be gratified that, at long last, the project is underway.

The benefits of ETCS compared to conventional signalling have been regularly stated and research has shown some of the typical situations:

- Emergency speed restrictions – trains will not slow down earlier than necessary, typically saving 24 seconds;

- Approach to stop signals – a much faster approach will be permitted with an estimated gain of 45 seconds;

- Late signal clearance – the DMI indication will come much earlier in all visibility conditions, estimated to be worth 1 minute 30 seconds;

- Late level crossing closure (the ECML still has too many crossings) – more pronounced than signal clearance, worth 2 mins 25 secs;

- Approach control for fast-to-slow line movements (modelled on Huntingdon) – much quicker slowing down profile calculated at saving 1 min 39 secs;

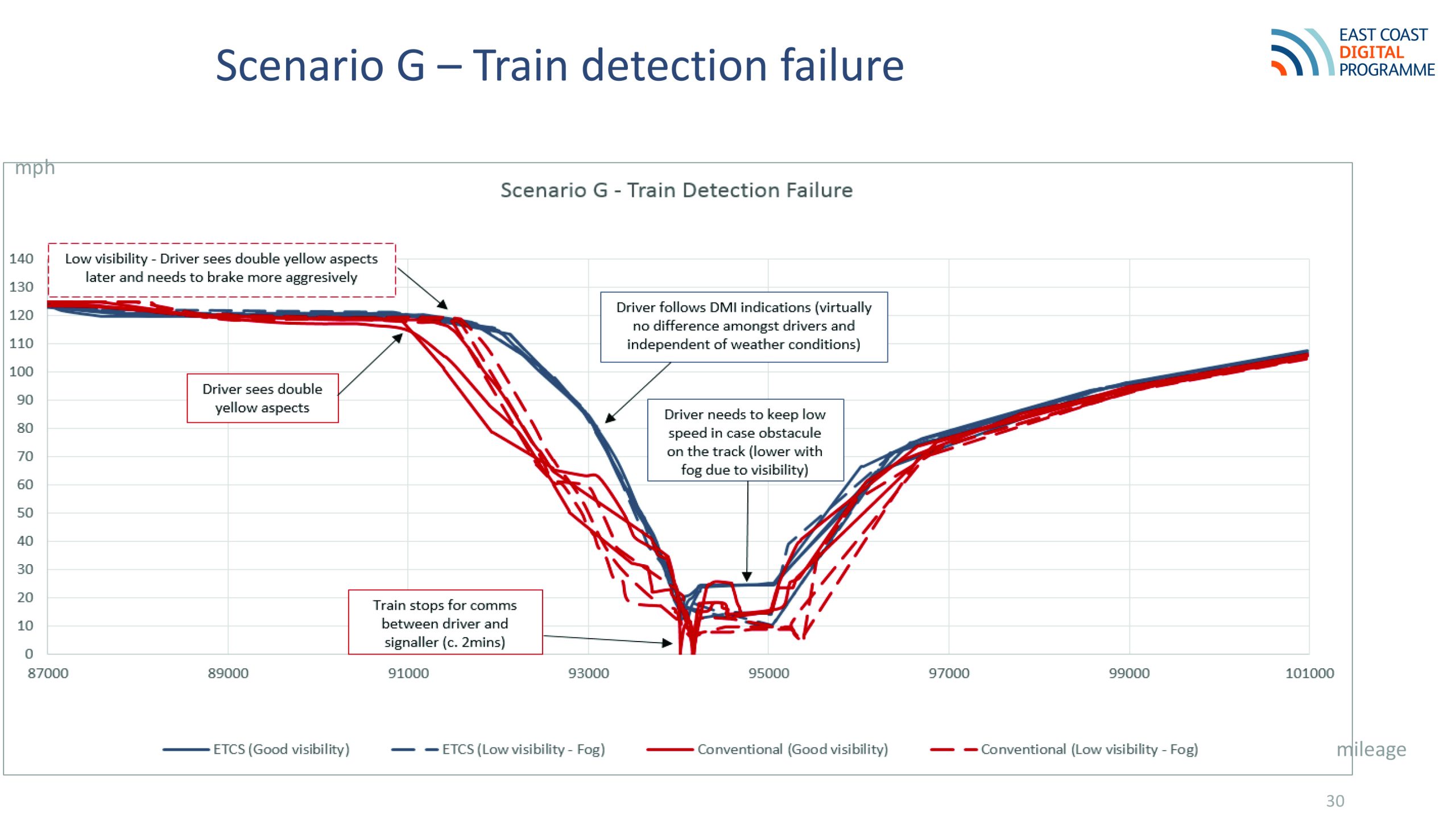

- Train detection failure (track circuit fault) – train will be significantly slowed, then given a proceed instruction by radio verbal message without the train having to stop, resulting in an estimated time saving of 6 minutes 57 seconds compared to present operational practice.

ETCS simulators have been in use for some time (issue 145, Nov 2016) and the conditions outlined are obtained from consistent driver modelling.

Currently, the ECML suffers 44,000 minutes of unattributed delay in a year, affecting 3,950 trains with an average of 11 minutes delay per train.

Delivering these changes will need people at the core rather than technology. Business change managers are appointed for each TOC, including a User Design Working Group with trade union participation.

Fitting the fleet

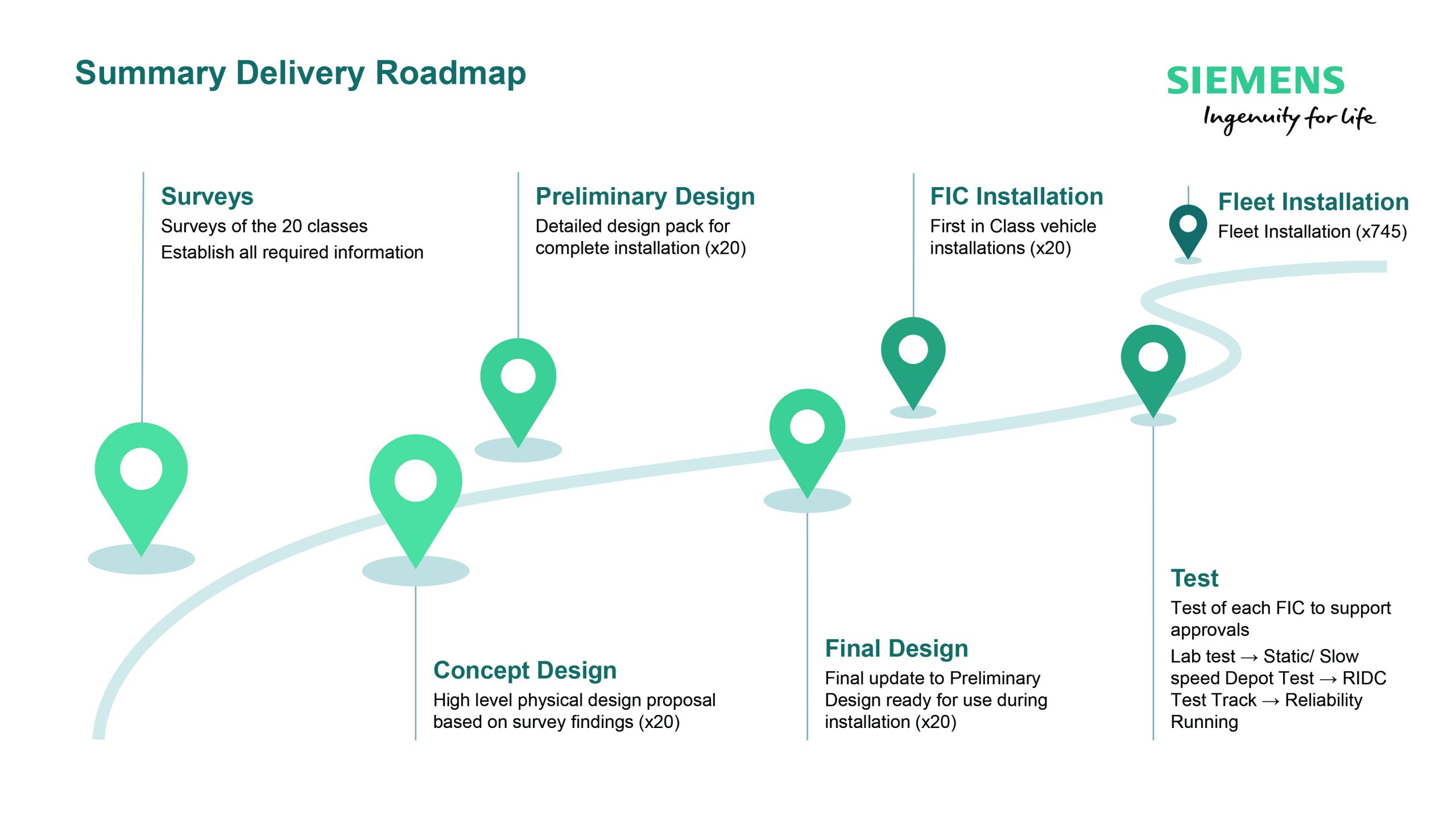

One lesson from the Cambrian early deployment was to try and avoid retrofitting existing rolling stock. Whilst all new trains since 2012 are supposed to have been built ETCS-ready (involving mainly passenger vehicles), Ewan Spencer from Siemens Mobility explained the challenge for freight. There are 745 locomotives in 20 classes (often with sub-classes) having an age range of between 2 and 50 years. Multiple ownership across each class complicates the situation. The lack of information and drawings for the older locomotives does not help.

A survey of all classes is the starting point from which comes a:

I – Concept design

II – Preliminary design

III – Final design

IV – First in class fitment

V – Laboratory test

VI – Static test followed by test running on the RITC (Old Dalby test site)

VII – Period of reliability running

VIII – Fleet installation.

It looks complicated but some of these stages can be quite short if things go well.

As well as the ETCS equipment, including the balise reader and the DMI, locomotives also need Doppler radar, a tachometer, brake and traction interfaces, a judicial recorder, speed displays and the installation materials. Quite a shopping list.

Progress so far is that work on 16 out of the 20 classes is underway, with the Class 66 and 67 preliminary designs complete. The Covid-19 pandemic has caused delays, as depot access is difficult.

What if it fails?

No matter how reliable a system, failures will always happen and signalling failures can be very disruptive.

Rail Engineer covered the progress of DMWS (Degraded Mode Working System, previously known as Compass) on two occasions – in issues 129 (July 2015) and 162 (April 2018), the latter describing a preliminary proving trial on the ENIF Hertford loop site. The idea is to independently prove a train’s position and that the track ahead is safe to proceed, then to issue a movement instruction to the driver via the GSM-R radio.

Karl Butler-Garnham, the Programme Manager R&D in Network Rail, reported that a full operational trial site has been selected – Westbury to Castle Cary – and is planned for 2023. Many organisations will be involved including Altran, Siemens, Mott Macdonald, Ebeni, PA Consulting, RSSB and NCB (Network Certification Body), after which a wider deployment plan will be produced.

One could be forgiven for thinking that the process needs streamlining if a relatively simple and beneficial innovation like this takes eight years from concept to an operational trial. Maybe this demonstrates the problem of implementing innovative ideas.

Rail Technical Strategy

The Network Rail technical strategy, dating originally from 2012, is shortly to be refreshed and aligned with the Digital Railway. It will be more compelling and will take account of business need. The move forward from ETCS Level 2 to Level 3 will feature for capacity gains since it envisages moving block. However, Level 3 is proving elusive across Europe, mainly because of train completeness assurance, so a Hybrid L3 version is being pursued. In addition, ATO as an overlay to Level 2, now in successful operation on Thameslink, will be part of the strategy.

Andrew Simmons described the benefits of the Hybrid variant, namely that passenger trains, where completeness is self-contained within the train data bus, can be given movement authorities for shorter block sections, thus allowing similar trains to operate with closer headways. Any trains not fitted with Level 3 equipment would continue to operate with Level 2 rules for safe distancing.

This does mean the retention of track circuits and/or axle counters. A full description of Hybrid Level 3 was given in issue 151 (May 2017).

Another innovation in development is the ETCS Level 2 Limited Supervision Overlay. If trains are fitted with ETCS equipment, but are not operating in an ETCS fitted area, can the TPWS speed indications be used to interface with the driver’s ETCS DMI?

When a TPWS overspeed condition is encountered, the train will brake, but the braking profile for that train is not known and the train may not stop before the red signal or within its overlap. By linking a TPWS ‘signal aspect sniffer’ to the ETCS on-board equipment, the braking profile becomes known and the train will stop more accurately, with incremental benefits being obtained.

A full prototype testing of both Hybrid L3 and L2 Limited Supervision will take place at the ENIF site in the period 2021/22.

Supply-chain perspectives

Getting industry on board is crucial and both Andrew Stringer and Rob Morris from Siemens Mobility (based in Chippenham and with the pedigree of the former Westinghouse Brake and Signal Co) indicated the necessary commitment. ETCS has been a long time coming, its first baseline being as far back as 1996.

What, however, does success look like? How many more trains per hour can be operated? Will there be enough trains?

Don’t overplay safety, since the UK is already the safest in Europe. The need to convince signal engineers of ETCS benefits is a fundamental factor! The ‘Sector Deal’ now in place includes the supply chain as much as the rail companies and Siemens, with others such as Alstom and Thales, will be major players. The portability of the programme should already be established through the EU interoperability rules.

The technology is proven, but will passengers actually notice? What will they be able to do that they cannot do now? Will digital technology result in a genuine ‘walk up’ service?

The biggest problem with signalling projects is delivery, when access is crucial and increasingly hard to get and ever more expensive.

Alterations to existing signalling (stage works in old speak) is a particular challenge and new interlockings, coupled with point machines and signals brought up to modern standards, may be needed, even if only used for a couple of years or so.

The five-year delay to ERTMS is proving a real challenge for existing equipment. That said, industry recognises that ETCS is the only way forward.

Long-term deployment plan

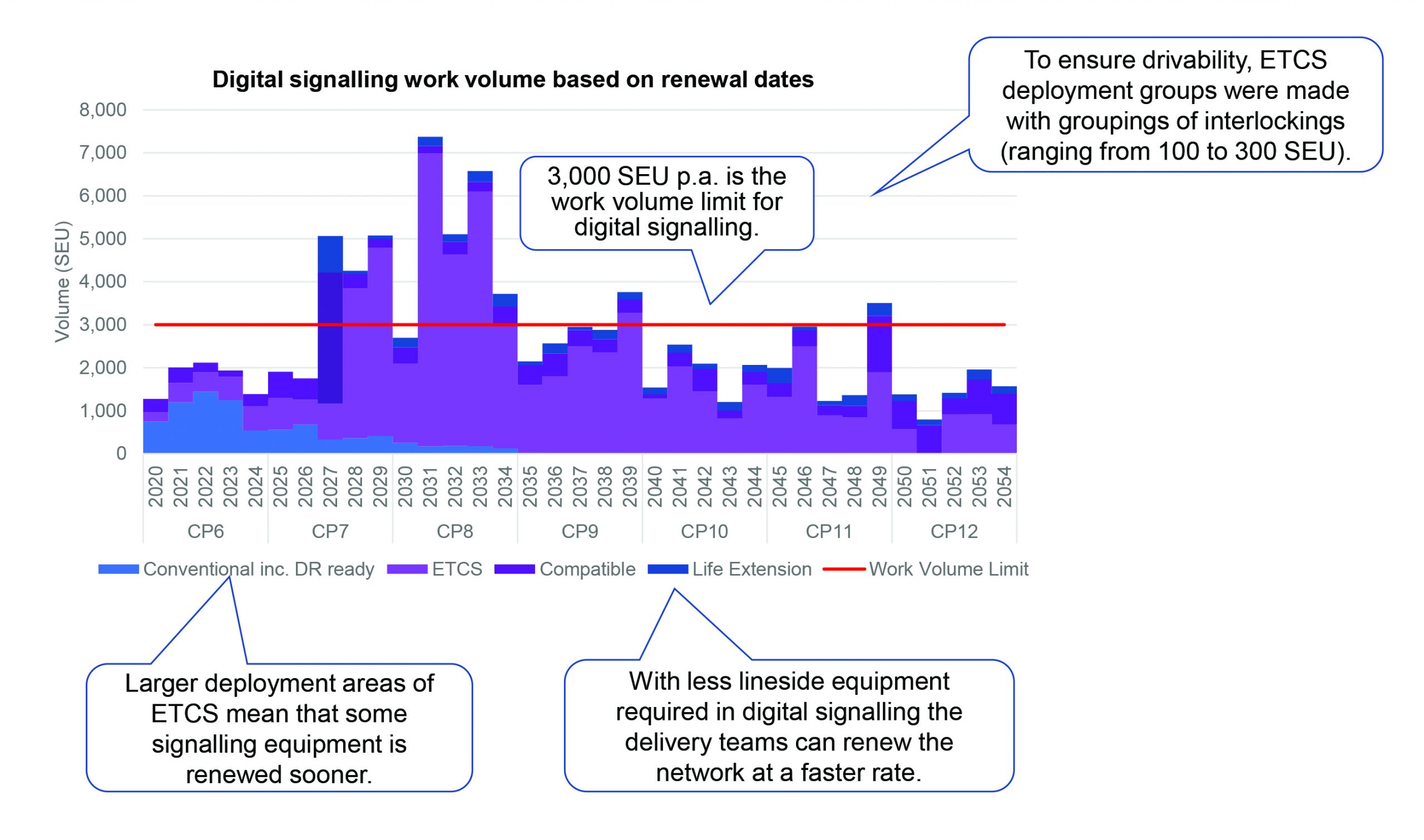

The ever-decaying life of existing signalling assets is causing concern. Network Rail plans for about 2,000 SEU (Signal Equivalent Unit) renewals each year, but the need often exceeds this, according to Pat McFadden, the Head of Technical Policy and Strategy at Network Rail. A budget of £830 million per year for renewals is in CP6, but life-extension work on existing equipment means this figure will be exceeded.

ETCS offers significant reductions in annual spend from 2035, but an increase in expenditure will be needed between now and then. Infrastructure spend will peak in 2027 and train fitment is a significant cost up to 2031. Only seven per cent of the fleet is fitted currently, with a further 40 per cent ready for fitment. New vehicles will account for the rest.

3,000 SEU renewals per year is the maximum that can be achieved with digital signalling. In Europe, the cost of an SEU is £190,000, but the UK does not yet match this.

CP7 will see the run rate build up, early schemes being Peterborough – Ely – Kings Lynn, the Midland main line starting in the Bedford area and the WCML north of Warrington. Scotland will come later and will be subject to separate government discussions. Wales is substantially equipped with modern conventional signalling, so will also be later on in the programme.

Martin Jones, the Chief Control, Command and Signalling Engineer for Network Rail, added comment on the £190,000 SEU cost, to be known as Target 190plus. The long-term plan shows 29 projects which need a standard architecture, with no bespoke solutions allowed. Access to industry will be required, which Network Rail is prepared to pay for.

The main benefits of 190plus will not be realised for 10+ years, so the industry must attempt to get some benefits earlier. Changes to the planning system are envisaged:

GRIP 1-4 will require a better toolset to promote improved early planning;

GRIP 5-7 needs to produce a ‘synthetic environment’, such as testing with far less disruption;

A Commercial and Sourcing strategy to improve engagement with suppliers.

Those of us who can recall projects at the height of the 1950/60s modernisation plan, will remember that there was a very close relationship between BR and the signalling industry. It worked well and the delivery rate was remarkable.

The role of SMEs

Just what can Small and Medium-sized Enterprises offer to the Digital Railway initiative? A number put forward ideas.

Lucy Prior from 3Squared considered that, whatever the digital railway turned out to be, the people who design and maintain the resultant systems will need enhanced training and re-assessment. Getting front line staff to understand what it is all about is a challenge and specialist firms in this field can play a useful role.

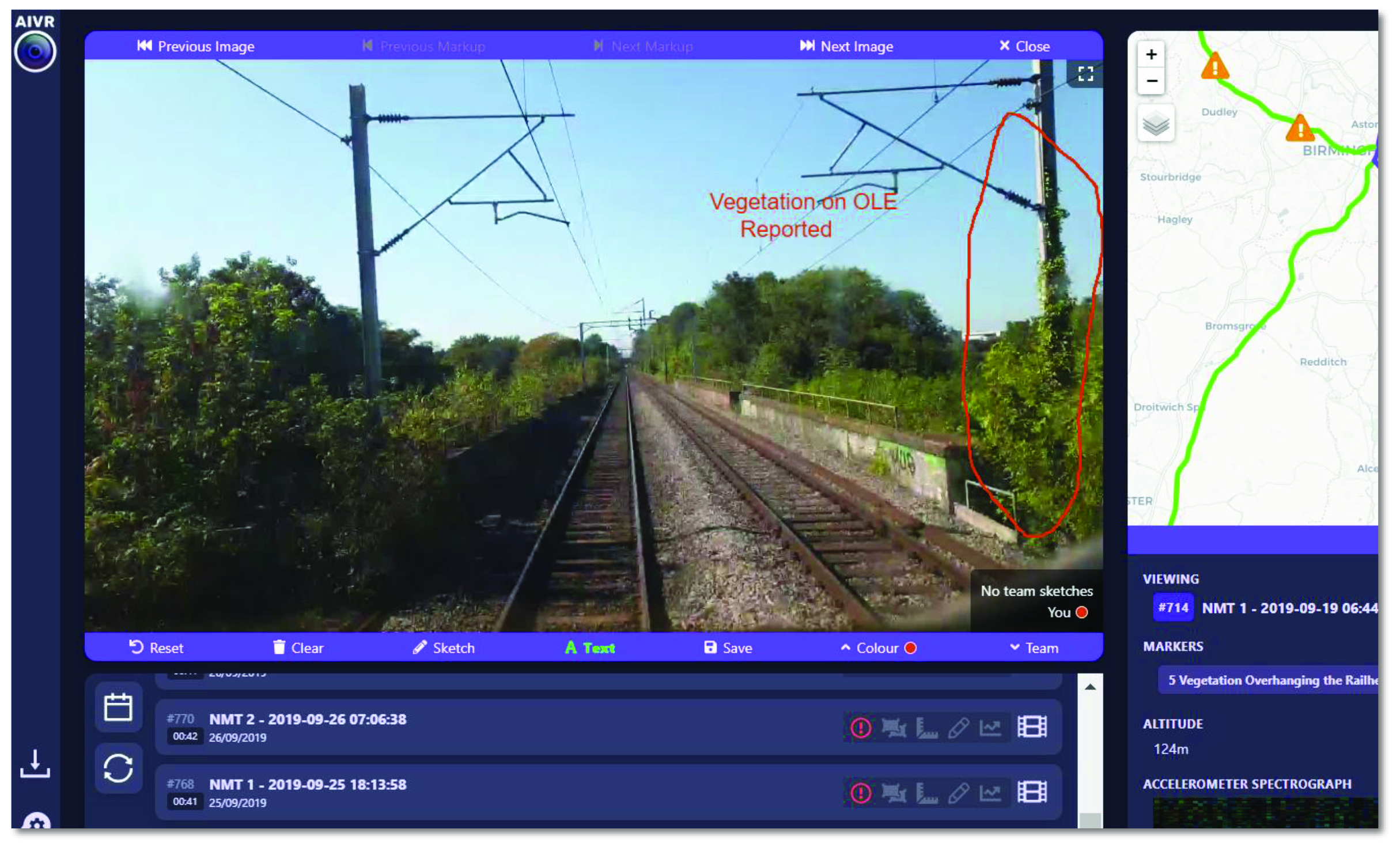

Emily Kent from One Big Circle, a Bristol-based company with a background of video imaging, is working with the Signalling Innovations Group (see below) to provide video capture of trackside assets from any operational train. A project known as AIVR (Automated Intelligent Video Review) aims to transmit packets of data continually using integral onboard processing. Knowing the minute-by-minute state of the railway will be a vital input to future digital systems.

Martin Pocock from Oakland Group, a company specialising in data analytics and new to rail, considered how to reduce risk in major programmes. Re-stating ‘loads of data but no knowledge of how to handle it’, a combined architecture designed to work with real project data would bring real benefits. Projects often run late because project managers and engineers failed to see what was coming. The claim that an 82 per cent improvement in a nine-month project forecast must be worth investigating.

Simon Rodgers from Oodl considered that a digital railway could benefit from ‘patterns of machine learning’. A record of all that is happening on a train – temperature, air conditioning, pollution, cleaning routine, ride quality and such like – would give prompts if any events or actions are missed. Oodl would be interested in seeking an industry partner to exploit its skills.

Stephen Bull from Ebini offered an independent safety assessment of innovative ideas to give an early indication of those that will succeed and those that should be abandoned. The company’s work with the DMWS system has been mentioned.

Contracts already exist with the main signalling suppliers under the Major Signalling Framework Agreements that provide an easier work progression for signalling renewals in the various Network Rail zones. Engaging SMEs to participate in these contracts is encouraged but is not always easy.

David Maddison from Alstom indicated that 20 per cent of its total spend goes direct to SMEs and a further 40 per cent via Tier 2 contractors. The route for greater SME involvement is to understand where the big companies are struggling and to suggest how a particular skill or product can help. Choosing the right time to engage is key to success.

The Network Rail Signalling Innovations Group, led by David Shipman, is not an SME but it does produce innovative ideas for the future of signalling and the digital railway. It has to ‘sell’ these ideas to other parts of Network Rail. A Rail Engineer article on the group’s work was published in October 2019 (issue 178).

Building a relationship with SMEs is seen as important, to analyse and value many of the ideas being put forward. This can assist the eventual placing of orders and provide ongoing monitoring on how well a product is developing and performing. Network Rail invariably struggles to understand the value of an SME, with often a resistance to new ideas.

Can academia help?

Anyone who read my recent article on HS2 (issue 183, April 2020) will have noted that Leeds University is equipping itself with a comprehensive rail research department and Birmingham University is similarly geared up for rail innovation. Jenny Illingworth spoke of the latter’s new Centre of Excellence for Digital Systems which is nearing completion.

Professor Clive Roberts and his Birmingham team are working jointly with the Thales Technical Services Group to create ‘digital twins’. The present uncoordinated practices, which lead to limited data sharing and different tools by different companies when working on new innovations, is a problem.

The digital twin idea, used successfully in the aerospace and maritime industries, creates a digital version alongside a real system that then allows a backward and forward movement of data between the two. Developments are undertaken firstly on the virtual system, then transferred to the real system with results and requirements fed back into the virtual system to make changes, and so forth. The resulting data is useful for future decision making.

A digital twin is being worked up for the West Midlands Railway, covering Crewe to London plus all cross-city routes around Birmingham, which will provide simulations and a ‘synthetic’ environment model. The intention is to give confidence to Network Rail and bring other suppliers on board.

Robert Hopkin, the head of educational development at Birmingham University, emphasised the need for training of specialist engineers and IT personnel by means of postgraduate courses. As well as MSc courses in Railway Systems Engineering & Integration and in Railway Control, shorter ones in digital leadership are being prepared, which will include overseas visits to gain a wider appreciation. Eight modules are envisaged, of which two will be available in early 2021.

In summary, RIA can regard this webinar as successful. Bringing sense to the digital railway concept was a challenge. Innovation takes many forms – it is as much about business processes as it is about new technology. Whilst the ECML project was the principal topic, novel ways of making rail operations more efficient were evident. Above all, it is the pulling together of all parties involved that will determine the programme’s ultimate success.